Of the three mural schemes completed by Gilbert Spencer, one has since been covered over and another is in a private building, so his significant contribution to the genre in the twentieth century has been largely overlooked. Gilbert himself greatly valued the opportunity to carry out a coherent scheme on a large scale. He was partly inspired by his brother Stanley’s Sandham Memorial Chapel at Burghclere in Berkshire (1927-32, NT), where his scenes of quotidian wartime activities were in turn inspired by Giotto’s frescoed Scrovegni chapel in Padua.

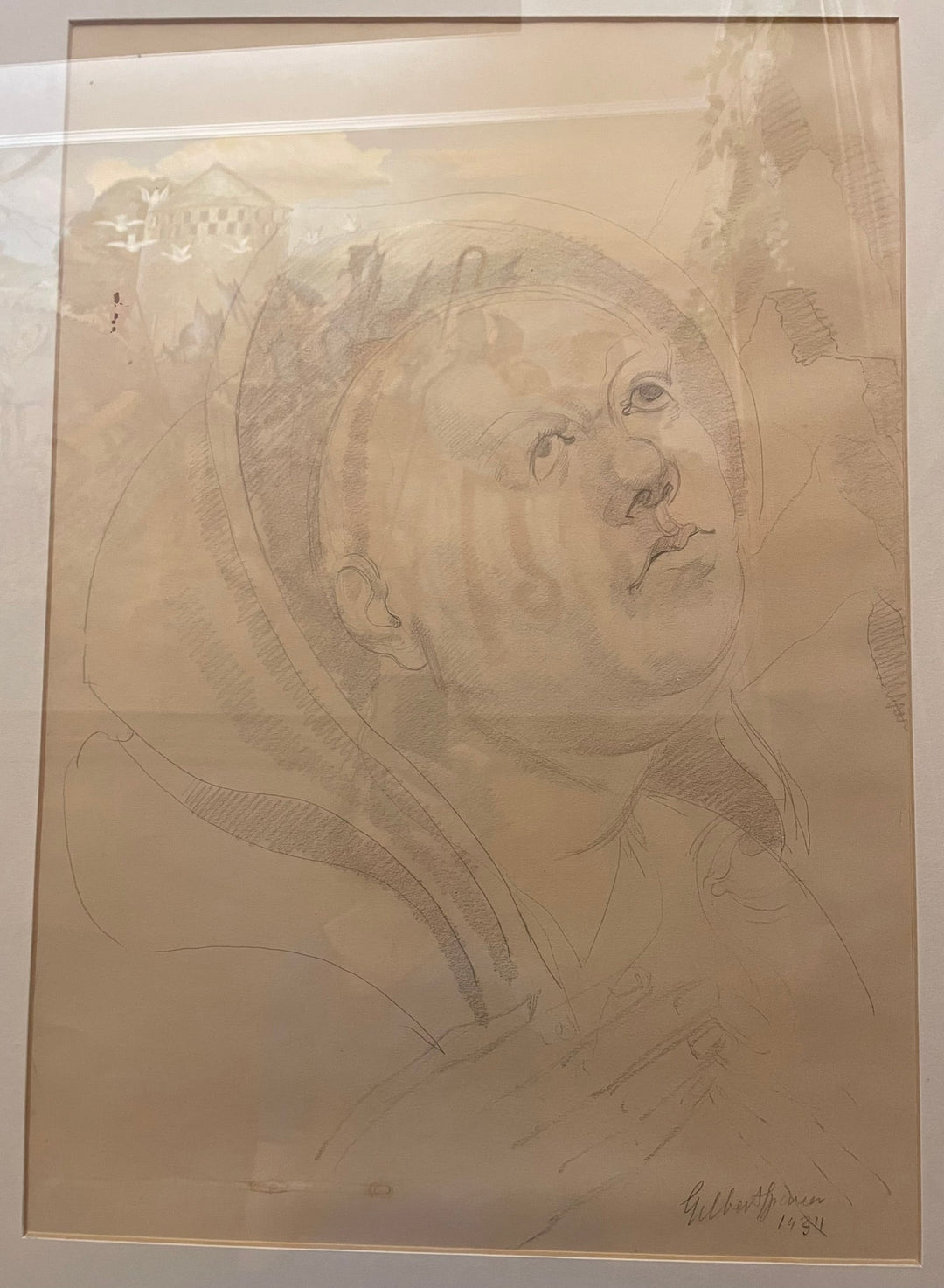

Stanley’s work at Burghclere was still in progress when Gilbert was given his own first mural commission. Entirely on the strength of A Cotswold Farm, Gilbert was commissioned by Kenneth Bell, a Fellow at Balliol College, Oxford, to paint the four walls of the students’ Common Room in the college’s new undergraduate accommodation at Holywell Manor. He began work in early 1934, moving with Ursula to Oxford, where they would spend two happy and productive years. A scale model of the design was exhibited at the Leicester Galleries that year (no. 40) and at Reading in 1964 (no. 43) (c. 1934, Balliol College, Oxford), while four working drawings were exhibited at the Leicester Galleries in 1939 (nos. 37-40) (Bishop’s Head/Monk’s Head, 1934, Balliol College, Oxford). Correspondence in the Gilbert Spencer Archive refers to the development of the mural (Gough, 2024, pp. 205-17).

The designated subject was The Legend of Balliol (1934-6, Balliol College, Oxford), summarised by Gilbert thus: ‘John Balliol wishing to possess lands belonging to the Bishop of Durham, ambushed him as he was crossing a ford. The Bishop complained to the King of England, and was released, John himself being arrested, was tied to a tree and thrashed. Dervorguilla, his wife, feeling that he had not done sufficient penance, gave money to sixteen poor scholars to come to Oxford.’ Gilbert’s narrative unfolded across a series of linked scenes: the ambush; the whipping; Devorguilla’s gift; the progress of the scholars to Oxford; the scholars studying in the chained library (appropriately, the room functions as a study space today). It was the first time Gilbert had worked on such a large scale, and he soon learned that patience was of the essence, methodically transcribing his squared-up drawings to the fresh plaster. Nevertheless, he brought a playfulness to this tale of violence and retribution. Chickens (one of Gilbert’s great strengths) strut and preen amid the protagonists. Unafraid of anachronism, he replaced the medieval ox-carts with his familiar farm wagons, and inserted lacrosse sticks and cricket bats among the scholars’ luggage, which is labelled with the names of resident Balliol Fellows.

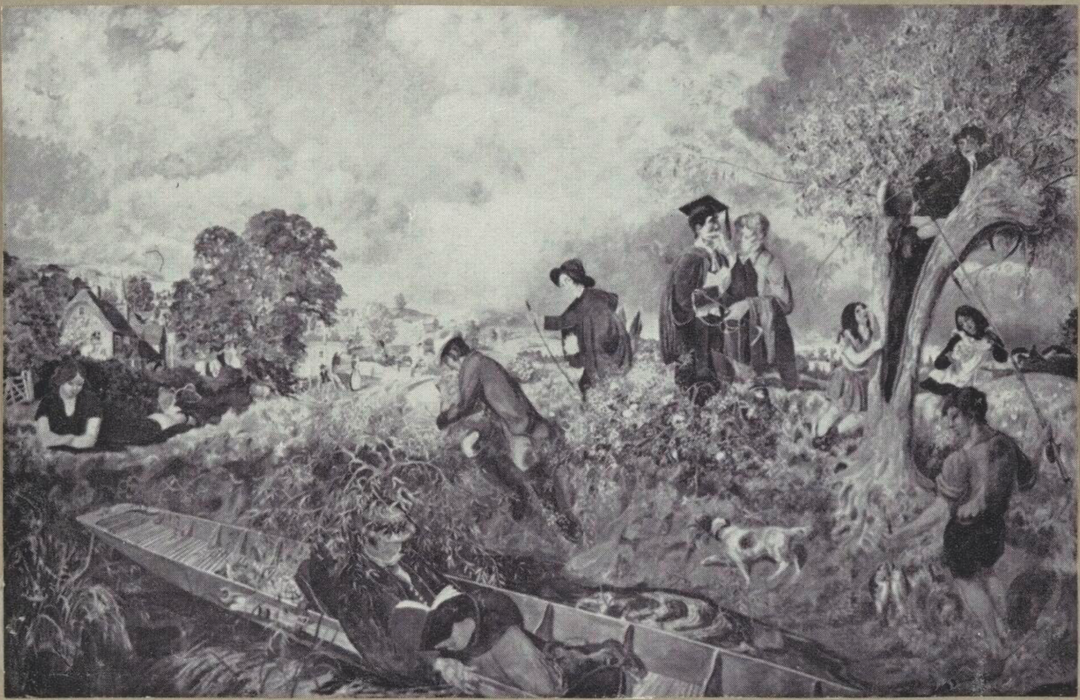

Two decades later, in 1954, an abortive commission from the Abbey Trust to paint a mural panel for Lincoln Cathedral (the project was abandoned) led to a second commission by the Trust to paint a wall in the new University of London Union building on Malet Street, Bloomsbury. He was allotted a wall of just over 10’ x 15’, for a fee of £465. Gilbert’s subject was taken from Matthew Arnold’s 1853 poem The Scholar Gypsy, suggested by Ursula, who had been reading the poem aloud in the evenings at Tree Cottage, their home in west Berkshire. Gilbert’s painting, The Scholar Gypsy (A Reference) (1954-6, University of London, since covered over) relates the tale of an impoverished Oxford student who leaves his studies to join a band of travelling gypsies. He learns their lore, and when he is recognised by two of his former Oxford associates, reveals that the travellers ‘had a traditional kind of learning among them, and could do wonders by the power of imagination’. As with The Legend of Balliol, Gilbert painted the story in episodic format, but this time he inserted himself into the mural as the scholar-figure, as well identifying himself as an Arnold-figure, who observes the scene from a punt moored in the stream. The Students’ Committee, reviewing the work in progress, requested some changes, and Gilbert agreed to add a female undergraduate (‘undergraduette’, as he called them). Sadly, the mural was later covered over and is now known only from photographs and through his correspondence.

Gilbert’s satisfaction with his achievement at University College was marred by a subsequent dispute with the Abbey Trust (administered by the Royal Academy) over his pay and expenses. This led to a partial compromise in the shape of an invitation in 1958 by Sir Charles Wheeler, President of the Royal Academy, to paint the end wall of the Royal Academy’s restaurant in Burlington House. He was to receive the handsome sum of £1000, paid from the Leighton Fund, and Gilbert, although dismissing it as a ‘nearly a pot-boiler’, admitted that he ‘found quite a lot to interest me in it.’

An Artist’s Progress is the most overtly autobiographical of Spencer’s works, following his career from childhood to the present day, happily on the upward trajectory of Bunyan’s Pilgrim rather than the downward plummet of Hogarth’s Rake. Gilbert’s recognisable figure appears in multiple vignettes, from a young boy sketching in bed (Cookham High Street behind him, little changed today), to the Slade, exhibitions, mural painting, ‘and finally to the Academy where on the extreme right of the wall I painted myself entering the council room to sign the Roll on my election’. Presumably this referred to his election as an Associate Member in 1950, as he was not elected a full Academician of the Royal Academy until 24 April 1959, days before the finished painting was exhibited at the Academy’s annual Summer Exhibition (no. 503). It did not find favour with the critics, one dubbing it ‘The Worst Picture of the Year’, and another jibing that ‘If anything was calculated to warn youngsters against a career in art, this should surely achieve it.’ It has, however, stood the test of time rather better than other twentieth century murals, and as Gilbert’s only publicly-accessible mural, is a fitting showcase of his talent in this genre.